In the Absence of the Object

Michael Prokopow, 2021. COURTESY OF THE WRITER.

I.

When the COVID-19 pandemic took hold in the middle of March 2020, I made the decision to fly to London to be with family. As schools, colleges and universities shifted to online, I figured that I could complete my teaching responsibilities online. I had originally intended to travel to London in mid-April to research a book I was writing on the Turner Prize-nominated British artist Hurvin Anderson, who was born in Birmingham in 1965. I had arranged my research program for April, May and June, with the manuscript to be completed by October.

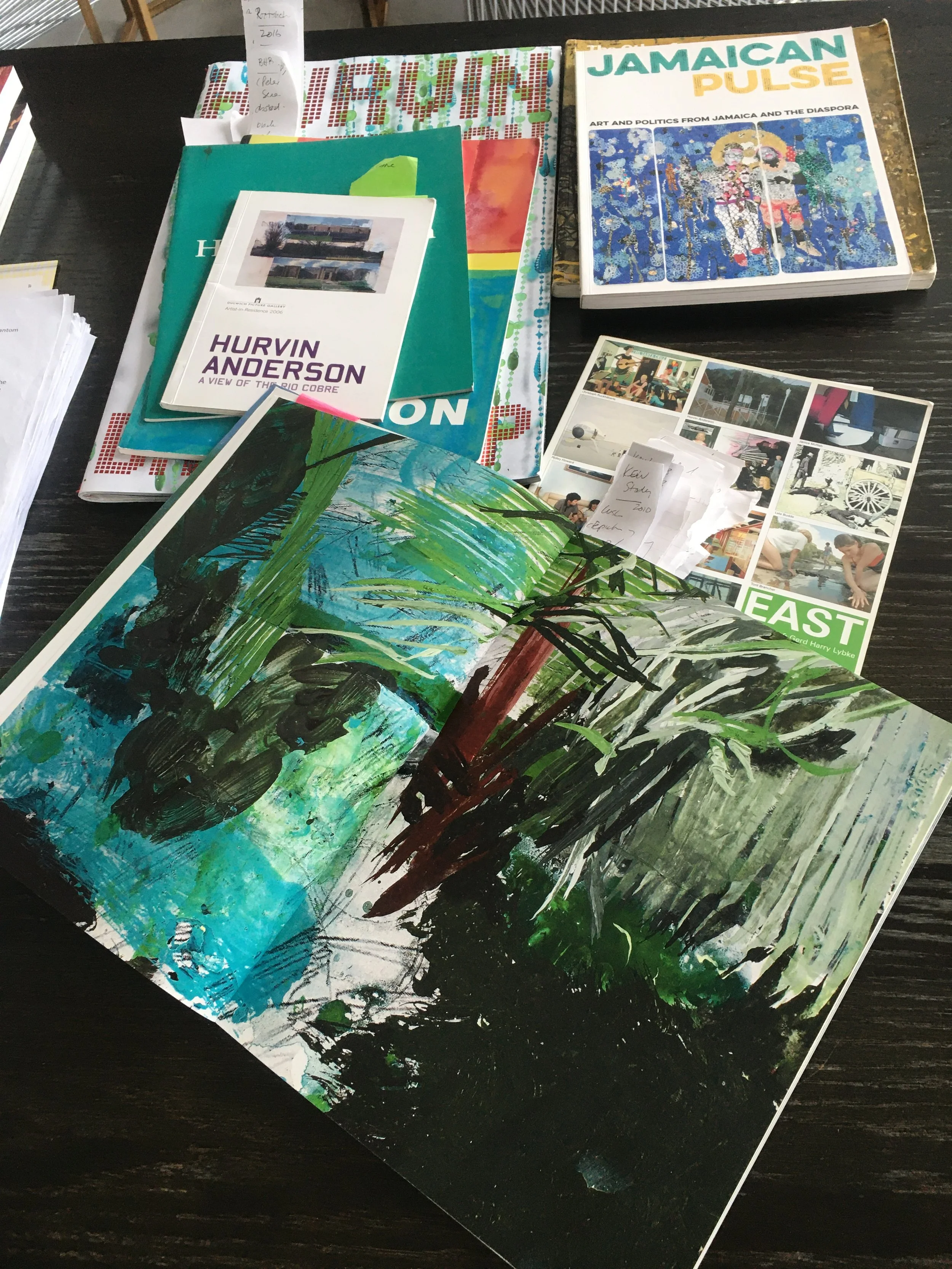

I used my baggage allowance to carry as many books and articles for the Anderson project as I could. While I had anticipated the lockdown of libraries and archives, I did not grasp the full implications of the pandemic. The institutions I assumed would reopen in a matter of weeks weren’t going to re-open before the end of the year.

My naiveté led me to assume that I could shift the appointments I had made to see Anderson’s work in galleries, museums and private collections. I had planned to take the bus to Tate Britain to use its serene art library where, on previous visits, I had established a productive routine of sitting and working at the same beautiful and quiet desk in a corner of the large windowless yet well-lit room. I was looking forward to visiting Anderson’s south London studio for what had become regular conversations over lager and crisps. During these visits, he would open his drawers to show me drawings, photographs and assorted objects.

I had also assumed that the work of writing the book would advance as planned once I had completed what I deemed to be sufficient and necessary research; this would have included an extended trip to Trinidad and Jamaica, which were important to Anderson’s work and life.

In hindsight, I couldn’t have predicted the extent of the suspension of everyday life. The library did not open again until late August (and then, haltingly, only for a few weeks), and all my thoughts regarding research and travel were sundered. My sojourn in London turned into a stay of 10 months. During that time, my editor made it clear to me that COVID-19 was not going to be regarded as a force majeure, and I would need to complete the manuscript by mid-October as per the contract.

Michael Prokopow, 2021. COURTESY OF THE WRITER.

II.

By the time I entered graduate school to study history, research was second nature: from locating primary sources in the archives and consulting secondary sources in libraries. As an undergraduate, I would visit the Provincial Archives of British Columbia. I went once to see a typescript copy of an early colonial account of the lower Vancouver Island when it was being leased by the Hudson Bay company. I had found out about the existence of the document in a journal article footnote — and I wanted to see it for myself. The typed words on the weathered pages constituted a portal to a different place and time.

I understood that a scholar needed to consult and master the literature of a subject area to gain a focused, precise understanding of the materials used in the making of the work.

In the archives, I learned that by locating the references used in secondary texts, and particularly the footnotes, I was participating in a culture of knowledge production and dissemination. I became aware of the obligations of research: tracking down a source, engaging with it, refining my thinking, and transforming knowledge into supported, empirically sound argumentation. I became immersed in a community of past and present scholars who shared my interests. I also became acculturated to a “life of the mind,” dedicated to the integrity of scholarship.

I have always predicated my work on exhaustive research. While working on my dissertation, I moved to London for 18 months so I could consult the holdings in the U.K. National Archives. I was investigating the ideological and material conditions of the Loyalists, the name given to adherents to the Crown in the American Revolution. The experience of about 120,000 people were recalled in several hundred volumes of the serial records at the Public Record Office (PRO), Kew.

I worked through all the volumes. The heavy volumes were consistent in size — around 10 by 18 inches, fragile pages hardbound in leather. I used foam rests and wore gloves, which I had to remove in order to write and type notes. Each day, I moved through as many volumes as possible. Often, I needed to request ancillary materials to corroborate something that was written or stated. My “reading” of each page in each volume included locating key terms: names of people, circumstances and the like. By the time I finished, I had a sweeping, detailed sense of the arena of conflict and the character and goals of British governance. I also collected remarkable stories of people’s circumstances and lives.

This research experience — along with work in other archives in Jamaica, Belize and the Bahamas — not only provided me with invaluable information for the writing of my dissertation, but affirmed in my mind the obligations a scholar has toward thoroughness.

III.

The COVID-19 pandemic changed everything, including how I approached research. I felt challenged by having to write a book about without doing everything I believed was necessary. Although it is assumed that the web is an equivalent to libraries and that it is advantaged by instantaneously offering vast amounts of data, the truth is that the undifferentiated information found through online searches needs careful and lengthy negotiation. Online information sites, like Wikipedia, neither provide the equivalent of libraries nor honor the rules of scholarly practice. There is a culture of responsibility that attends the production of peer-reviewed texts that ensures a higher level of accountability.

I knew I would not have access to the Anderson’s studio or archives, and I wouldn’t be able to get my hands on obscure journal articles and rare monographs. I decided that if I could not go to libraries, I would have to find alternate ways of gathering the information I needed for a critical accounting of Anderson’s practice.

The precision that had defined my work to date had to be pragmatically managed and negotiated, but the solutions I found online at least allowed the project to move forward. In the end, I purchased close to 100 books and managed to locate and download several hundred articles. However, I felt I was able to approximate the type of expanded research that marked by a way of working before the pandemic.

The lack of access to the artist’s works gave me the most anxiety. There is something vital about seeing an object, a painting or drawing in person. No matter how high the image’s resolution, being in the presence of a work of art affords an understanding missing from the digital encounter.

In his celebrated 1935 essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” German critic Walter Benjamin raises the matter of what he calls the aura, or power, of original works of art. The hand of the maker and a type of spirit of their presence is palpably present and significant. For Benjamin, the democratic, pedagogical promise of photographic images of works of art are in philosophical combat (perhaps too strong a term) with the power and autographic implications of an actual painting or sculpture.

Any close reading of Anderson’s physical works was incomplete, and I was not able to devote as much attention and discussion to the ways he made his paintings and their material realities. And although I did ask the artist about the type of acrylic he used and brush size and substrates, I eventually shifted my attention to talking about the narrative and critical subject matter and implications of his images.

Am I the poorer for not seeing firsthand more of the artist’s work? I am certain the answer is yes.

In the end however, I did produce a text that combined a discussion of Anderson’s work, career, early life and his vital significance in the context of contemporary British and Atlantic art. I considered themes and subjects considered by Anderson in his practice, such issues as: identity; trans- and multi-locality; the history of Caribbean emigration to Britain after 1945 (the Windrush Generation); the history of the enslavement of African peoples; the Anglo-Atlantic world; the histories of empire and of colonialism; the implications of decolonization; and what function as postmodern aesthetics.

This isn’t the book that I thought I would write. What I had planned to be a balanced consideration of the ideas that define Anderson’s work shifted towards an interrogation of what I term the postcolonial-picturesque as the sensibility that defines Anderson’s image making.

What I learned from my experience is that I remain responsible to the obligations of research and analysis. A degree of ingenuity is needed, alongside a willingness to think differently, pragmatically, creatively and outside the proverbial box that, in my experience, contains the archive.

And as Anderson told me, there will be a time when I can get back to the library and into his archive. For while every project has to be completed, the work of investigating the world and sharing ideas is never done.

This article was published in the Spring / Summer 2021 issue of Studio Magazine